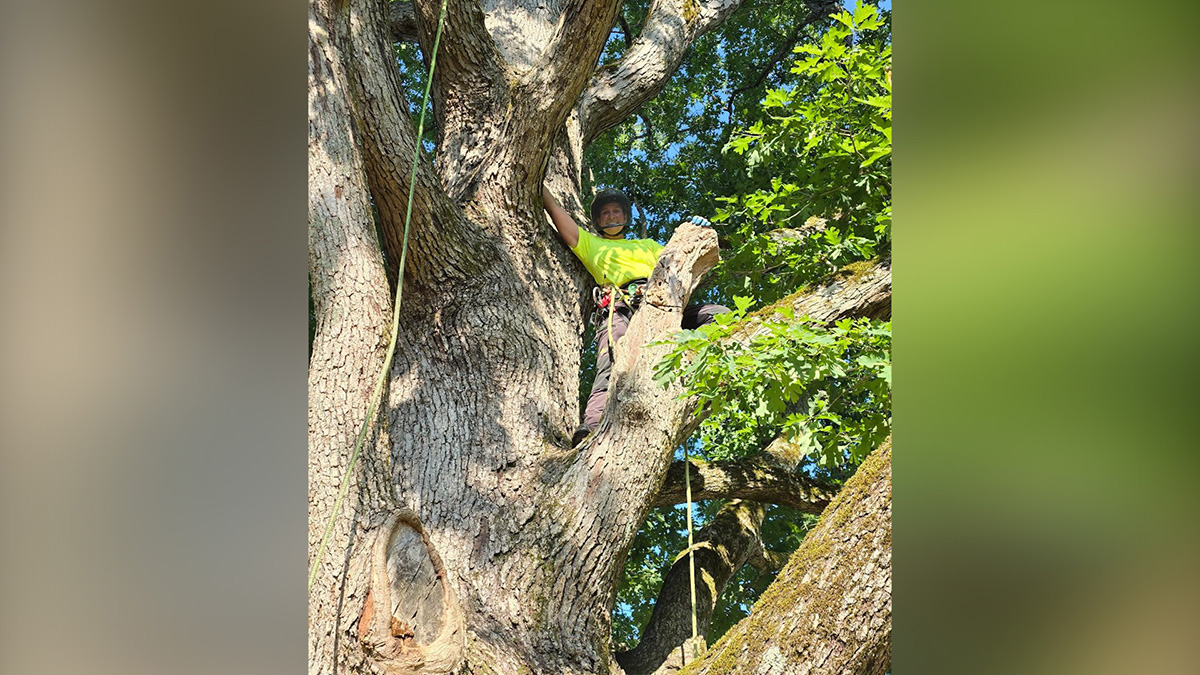

Graduate Teaching Assistant and natural resources doctoral student Mel Mount shared her research on developing a tool to improve tree risk assessment accuracy during episode 33 of the Step Outside series. Mount earned her master’s degree in forestry at UT. She also owns her own tree company, Treecology. You can watch the full interview below or on our YouTube channel.

Could you give a quick summary of your research into utility vegetation management?

I’ll try not to go too longwinded here, but like anybody else, I enjoy having power and staying warm at this time of year. I am a certified arborist, and I have a tree risk assessment qualification. I got that a year after becoming certified, and it basically asks what your experience with a species of tree is. I think I only have a year, and I don’t know. It’s kind of always bugged me, and I wanted to be able to have something more definitive, some quantitative thing to put on it to say that this tree is likely to fail. Of course, liking my power, the logical place to first start applying this is along our utility rights of ways to maintain that and especially along these corridors because they span hundreds of thousands of miles. This is normally something that gets done pretty quickly. Also, having the natural resources background, I don’t want to just cut down trees that don’t need to be cut down, but I like keeping my power too. Hopefully, the goal of this research is to be able to quantifiably be able to predict when a tree is likely to fail. That way we’re only cutting the ones that need to be cut, but also we’re helping improve the reliability of our utility networks.

When you talk about this research, walk me through how you’re hoping to get that information?

The first step is that we’re going to be sending out a survey to utility practitioners finding out if they’re noticing anything that needs to be particularly addressed. An example I’ve been using is if a lot of people come back and say, ‘Hey we’ve noticed oaks uprooting. We have no idea why.’ Then we could focus the research on areas that are heavily you know oak-dominated. That’s just an example. I don’t know that they are, but we’re going to send out that survey first, see if there’s any particular area that needs addressing, and from there, coordinate with a series of utility providers to be able to get this data. That’s kind of up in the air. Rather that looks like me and some other people getting the data ourselves or training people from these utility companies to make sure that we’re getting the quality of data that we want. That’s still up in the air at this point, but getting some infield measurements of trees that did fail and then being able to analyze it from there.

One of the things you mentioned is that urban foresters are kind of hesitant to adopt these new measurement practices. Why do you think that is?

Urban forestry is a field with people from various different backgrounds. Very few people in my experience started in urban forestry, and I think you have a lot of different people coming from a lot of different backgrounds. It’s not to say necessarily that they don’t trust each other. It’s just that level of feeling synchronized isn’t there, and I think there is hesitance on that part. It’s new. We like what we’re comfortable with, and to some degree, I think there’s some of the ‘this is the way it’s always been, why change it if it’s not broke,’ except maybe it’s not broke, but it still could be better.

Well, like you said, even though we’ve been doing it this way for a long time, there are discrepancies.

Yes. Initially, the tree risk assessment process started out being quantitative per se, and they found out that there were some mathematical, illogical fallacies that occurred. They did away with that and went more qualitative. Now, you just get a risk rating that’s you know low, moderate, high, or extreme, but extreme ones you don’t ever have to go through that process. It’s going to fail. It’s just kind of this general category and, depending on your level of bias, can influence these categories. My hope is to be able to take out some of the bias, and I have it too. I’ll acknowledge it. It is about Bradford pears. They get this reputation of being a really weak tree. They’re going to split out. I have that same bias. There’s actually been a paper that was produced that said they’re not actually any more likely to than anything else. Personally, I have a hard time believing it, but they had the data to back it up. There’s again that. I mean I’m seeing it within myself. This level of ‘I don’t know about that,’ and that’s just me as one person. When you get the whole industry that starts doing that towards things, then you know we don’t want to change what we feel we know, but I’m hoping the quantitative side will help have numbers to produce it, and we’ll start seeing a difference there.

I’m glad you brought up the example of the Bradford pear because that’s surprising. I would not expect that at all.

Personally, me neither, but that’s what they say. It doesn’t mean I like the tree. They’re probably my second least favorite.

What’s your first?

Tree of Heaven. Everyone has a different opinion for what they call the smell, but I think it smells like rotten peanut butter, and no I’ve never had rotten peanut butter, but if it could rot, that’s what it would smell like.

Yes. Both of those species in Tennessee are not welcome.

No.

Once you gather all the data and put it out there, what is your hope for how utilities will use it or how other urban foresters will use it?

My hope is to have some type of a program or form or whatever the final application is that any practitioner could use whether it is utilities or a private land manager. Not necessarily homeowners. You don’t want to have more information than you can feasibly handle, but for practitioners in the field to have this as a guide. When they’re looking at a tree if it’s somebody who is in the same situation as I was with a year’s worth of experience going into this, they can look at it and say, ‘Well, I’ve got this tree. Let me look at these different things.’ One example I have is that we know in science that co-dominant stems are weaker. Recently, they found the shape of the union makes a difference in how strong it is, but then my question with that is at what point is that a problem? A one-inch stem and a one-inch stem on a newly planted tree is probably not an issue. Is that eight inches? Is it 12? Is a species dependent? That’s some of the things I’m hoping to be able to determine. That way when you’re out there with one year of experience like I had you can go up to this tree and say, ‘I’ve got you know this species,’ and then measure the stem, or maybe it’s a range where you can eyeball it so this is something that gets quickly done. You say, ‘Well, I’m approaching that level. Maybe we should consider whether it’s a branch reduction or the whole tree needs to go,’ Whatever the case may be. It’s something to say this warrants either further investigation or mitigation instead of just what your biases about this tree are.

Do you think that will also make it easier for utilities or urban foresters to kind of look at a tree and make those determinations?

I think so. I think at first it’ll be a little bit harder because, like we talked about with the Bradford pear, there’s some of that. You have your own perceptions, and if the Bradford pear didn’t make this cut off, you’re going to say, ‘Well, it’s a Bradford pear.’ I think at first there’ll be some resistance towards it, but as more people would start to use it, you start getting results of I took this tree out, and we had less issues with the utilities this year. I think you’ll start gaining some ground. I think it’ll be slow at first, but ultimately keep us in power longer, or if it’s private companies using it, then I hope they’re not just cutting down a tree because I know there are companies in the area hesitant to keep trees they suspect might have any kind of issue because of the liability that would fall back on them if the tree were to fail. Hopefully, this has some scientific backing behind it that says this tree is probably not going to fall, and they can explain that to the customer and walk them through how they came to this process and be more sustainable for us all around.

Do you have any plans after getting your PhD, or is that too far out?

There are loosely some plans. I think ultimately that I do want to go into teaching. I had a professor who was really influential to me, and he had the academic side. He was my professor, but he had also spent a number of years in industry before being a professor. Now at this point, I only have four years in the industry. It’s not like that’s a lot, but I do also own my own tree company right now. It’s part-time. It’s not full-time work, but I get some experience in that as well. My goal is to hopefully be that person to someone else like he was to me and have some of the industry side but also teaching there is a proper way to do things and being able to be that person for somebody. What exactly that looks like at this point, I don’t know. What level necessarily or where, I don’t know. We’ll see kind of where that road takes me.

If you don’t mind sharing, what is the name of your tree company?

My tree company is Treecology, and it was a play on words of being trees and ecology.

When did you start that business?

I started it in February of 2022. I started my Master’s here in January of 2022.

Busy year.

Yeah, but I initially made it because going back to school was a pay cut, and it helps pay for the bills because I like eating.

Yes. Yes. You like eating. You like having a roof.

I like eating well too. That’s the real problem.

Don’t we all, honestly? I know you said you kind of do that on a part-time basis, but did starting that business kind of drive you towards what your research is right now?

Probably a little. When I started my master’s in forestry, I ran into Dr. Jean-Philippe one day in a hallway wearing an ISA shirt. She stops me and asks what do you know about ISA. This is the first time I’ve ever even talked to her, and I said I’m part of it. I’m not sure what the right answer here is, and from that moment, it just kind of got me thinking about it more. It was something I was doing part of the time, and I ended up taking one of her classes, Principles of Urban Forestry, because I decided I wanted to stay relevant. Climbing those trees, which I didn’t even know was a part of the class, but climbing those trees I realized that ultimately I didn’t want to give up that side of things. When you’re doing it part-time, and there’s all this other stuff going on, it does feel like work. You’re here to get the job done, and you’re just in and out, but being in the trees on campus made me realize that I really loved that side of it. If I hadn’t made the company in the first place, I don’t know that it would have had an impact. Seeing it from the side of not having to get in and out and having to rely on this paycheck was really influential to me, and that’s when I decided I didn’t want to give it up and started considering the idea of a PhD. I was told to pick a topic that I really felt passionate about because in this person’s words, ‘I would be married to it.’ I kind of started thinking about different things, and it always came back to tree failures. That was the thing that interested me, that I wanted to know more about. The utility lines and utility networks just seemed like a logical step because like you said I like eating well. I like having a roof over my head, and that also requires power. I mean not technically, but the comforts that go along with those things. I have one room in my house that isn’t heated nearly as well as the other. It’s a garage that got converted, and I went out to that this morning, and I said no, thank you.

This work is really important because it affects heating and cooking and just people’s lives. I think it’s great that this is what you’re researching and that it’s going to help make that tree risk assessment even better.

I think it’ll be beneficial to a lot of different people, and they might not necessarily realize it. You know the the average person isn’t going to know what their utility company is doing to maintain that power for them, but ultimately it’ll affect a lot of people if it’s all successful.