Imagine not relying on computers or word processing to write an academic article, but instead using a typewriter.

“Back then, things were a lot slower,” Scott Schlarbaum, School of Natural Resources professor and UT Tree Improvement Director, says.

Scott started working on refereed publications, or peer-reviewed articles, more than 50 years ago. He says, “If you started to write a paper for refereed journals, it would take maybe a year or a year and a half before it would appear.”

Refereed publications detail research methodology and results. People can find them in academic journals for a range of topics, including forestry. Scott got involved in undergraduate research at Colorado State University, which led to his first publication in Silvae Genetica in 1975. “At the time, it was the only journal for forest genetics,” Scott says.

He studied genetics under Professor Takumi Tsuchiya, a barley cider geneticist, who later became Scott’s major professor for his PhD. “I worked with barley for about a semester and he says, ‘But you’re a forester. Do you have any trees?'”

Scott was growing trees from giant sequoia seed and incense cedar seed he collected from a trip out to California. Professor Tsuchiya asked Scott what had been done on the trees’ chromosomes. When he said he didn’t know, Professor Tsuchiya told Scott to look through the biological and forestry abstracts. “Now, those were over in the library,” Scott says. “They were big, huge books with published abstracts of everything that had been published in the world.”

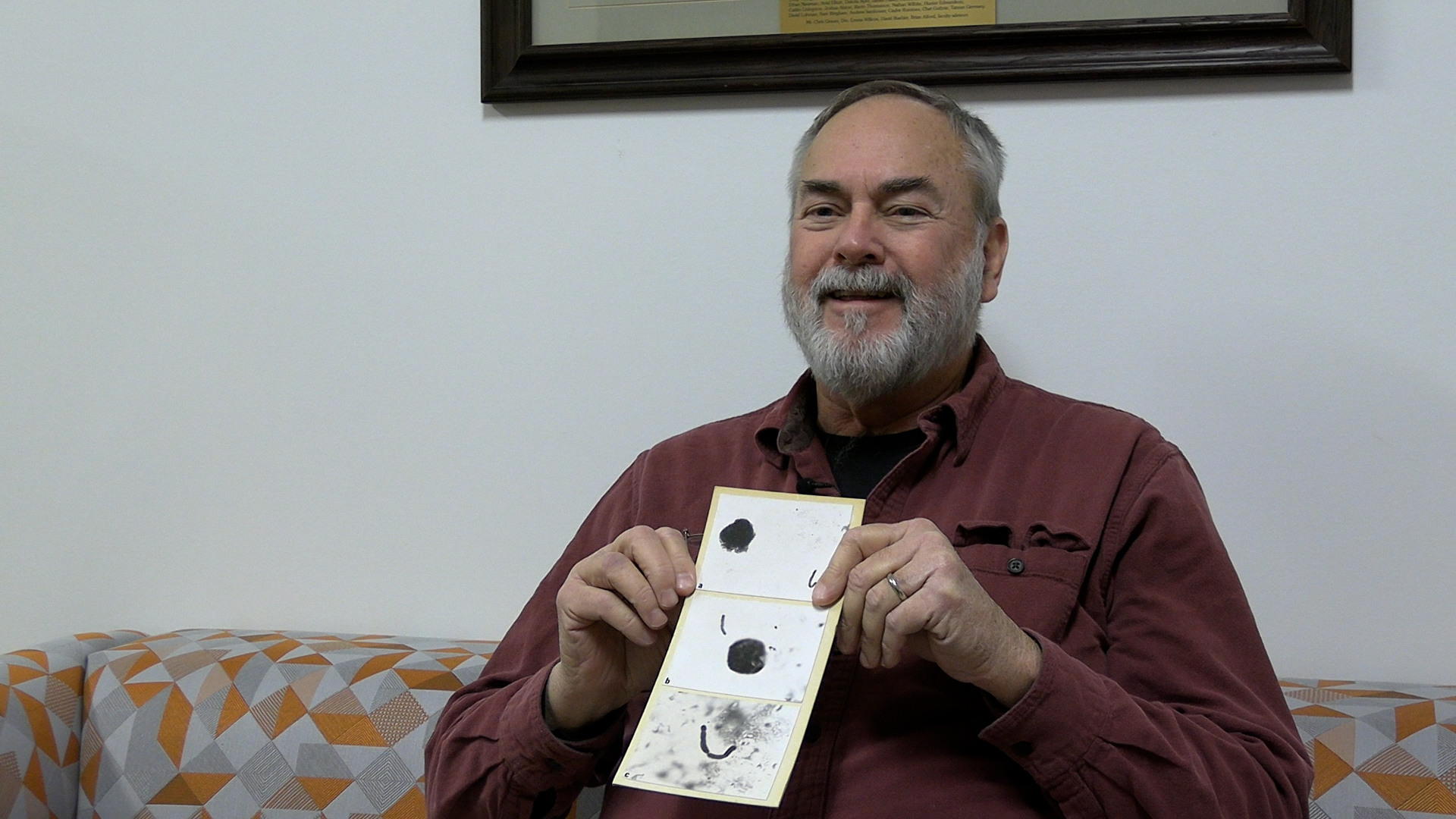

Scott spent days reading through books and determined no one had characterized the chromosomes. He made chromosome preparations, took and developed photographs, and worked on typing up a manuscript for publication. “If you made a mistake, you could retype that same note, and it would lift the ink off the page,” he says. Then, he would use a pasty substance known as Wite-Out to paint over the mistake and type the correct letter or word.

Scott would type up the first draft, correct it, and type it up again. This process repeated two or three times. He also developed images, figures, tables, and graphs. “We did all of our own photography,” Scott says. “You would put dry mount paper on the back of it, which is a paper that, when you apply heat, glues to the cardboard.” He then used Zipatone, which was adhesive shading sheets used to add texture or tones to artwork. It allowed him to put letters on the chromosome plates.

“You had to, of course, be very careful, get it exactly the same place, level, all of that,” Scott says. When the final manuscript was done and ready to submit, Scott says they would photograph some of the figures and submit the photographs or the original plate.

The manuscript then underwent the review process with more corrections. Once done, the printer sent a galley proof showing how the article would appear in the journal. Authors would review the proofs before they were printed. “They had a whole manual on how to edit the galley proofs,” Scott says. “If you made a mistake, you wouldn’t just correct it. There were printer codes, and there were symbols. You’d have to put that on the outside margin and show where it occurred. It was like a whole different language.”

Scott had to return the corrected galley proof within three days because the printer needed to set up their machine for another order. “They couldn’t leave it sitting around for two months waiting for you to make the changes,” Scott says.

More people started using computers in the early 1980s, but that wasn’t the case when Scott came to UT. He says in 1984, they didn’t have any computers and were still working on manuscripts the “old-fashioned” way. “Here’s your manuscript. You edit it, tear it apart, cut and paste, and give it back to the secretary,” he says. “You had a lot of paper files, a lot of space that went into that.”

Scott says people started using computers at UT in the mid-80s. By the early 90s, desktop computers and other tools made it easier to develop photographs and figures. “No more plate process and photographing things and Zipatone,” Scott says. “Those were all gone by the mid-90s.”

The process improved, but Scott wishes people spent more time reviewing publications. He recalls getting an article, going to the library, and checking if the references were correct. “Everybody’s so busy now,” he says. “I don’t do that anymore. I’m too busy. I have a feeling a lot of other people don’t do that either.”

Along with the other improvements, Scott appreciates the push to include undergraduate students in research and the publication process. The Herbert College of Agriculture offers the Herbert Experiential Research Opportunities Program. It supports undergraduates pursuing experiential research. He says, “I think the undergraduates have the opportunity through programs like that to have much wider exposure, much better training, much more opportunity to use their brains and practice the training they learned in class.”

Special thanks to UT Libraries for access to the Pendergrass Library and the Special Collections Reading Room.